How to Use

TOOLS

The project offers four research tools designed around the conventions described in the following sections. The research tools are as follows:

- Facet Search: This

search system allows scholars to synthesize information from the research

findings by searching for the number of extracts from each author

(“Plays by Author”), the number of extracts from each author

under a particular heading (“Authors by Subject”), the various

plays cited under a particular subject heading (“Plays by

Subject”), the authors cited under their various subject headings

(“Subjects by Author”), and the various subject headings

containing the extracts of a particular play (“Subjects by

Play”). The search results can be ranked either alphabetically (by the

title of the play or the name of the author) or by “Frequency”

(denoting the number of occurrences of each item listed from the most to the

least frequent).

- Edition Search: This

search method centres on three of the same search categories as the Facet

Search but breaks apart the particular records to include the specific

editions of the plays that Cotgrave used, rather than having that information

comprised under a single title (“Editions by Author,”

“Editions by Subject,” “Subjects by Edition”). It

links the search results to separate sections of commentary that synthesize

the textual findings for each edition, found in the Editions section

(). This

includes stating at a high level the features of the extracts that would

suggest their derivation from the particular listed edition.

- Source Index: This

hard-coded listing includes the source titles from Cotgrave’s

English Treasury, with links for the various extracts from each

play. It enables comparison of the results from the present survey with other

surveys, such as Bentley’s “John Cotgrave’s” and

Wiggins’s “How to Find Lost Plays.” Additionally, it

provides a simplified means of presenting together, with links to commentary,

the extracts that appear to be from lost plays, lost versions of known plays,

and those of critical interest for other reasons, found in the Extracts

section ().

Users can search for specific plays using the built-in search function of

their web browser to find a title and browse all primary titles listed in

alphabetical order.

- Subject List: This

hard-coded listing provides the full subject headings of Cotgrave’s

book, where his index offers only abbreviated headings simplified through one

subject term and omits a few listed headings, described below (). Similar to

the Source Index, the research findings of the Subject List can be searched

using a browser’s built-in web-search functions or accessed

alphabetically.

CONVENTIONS

The Case Numbers System

Pagination

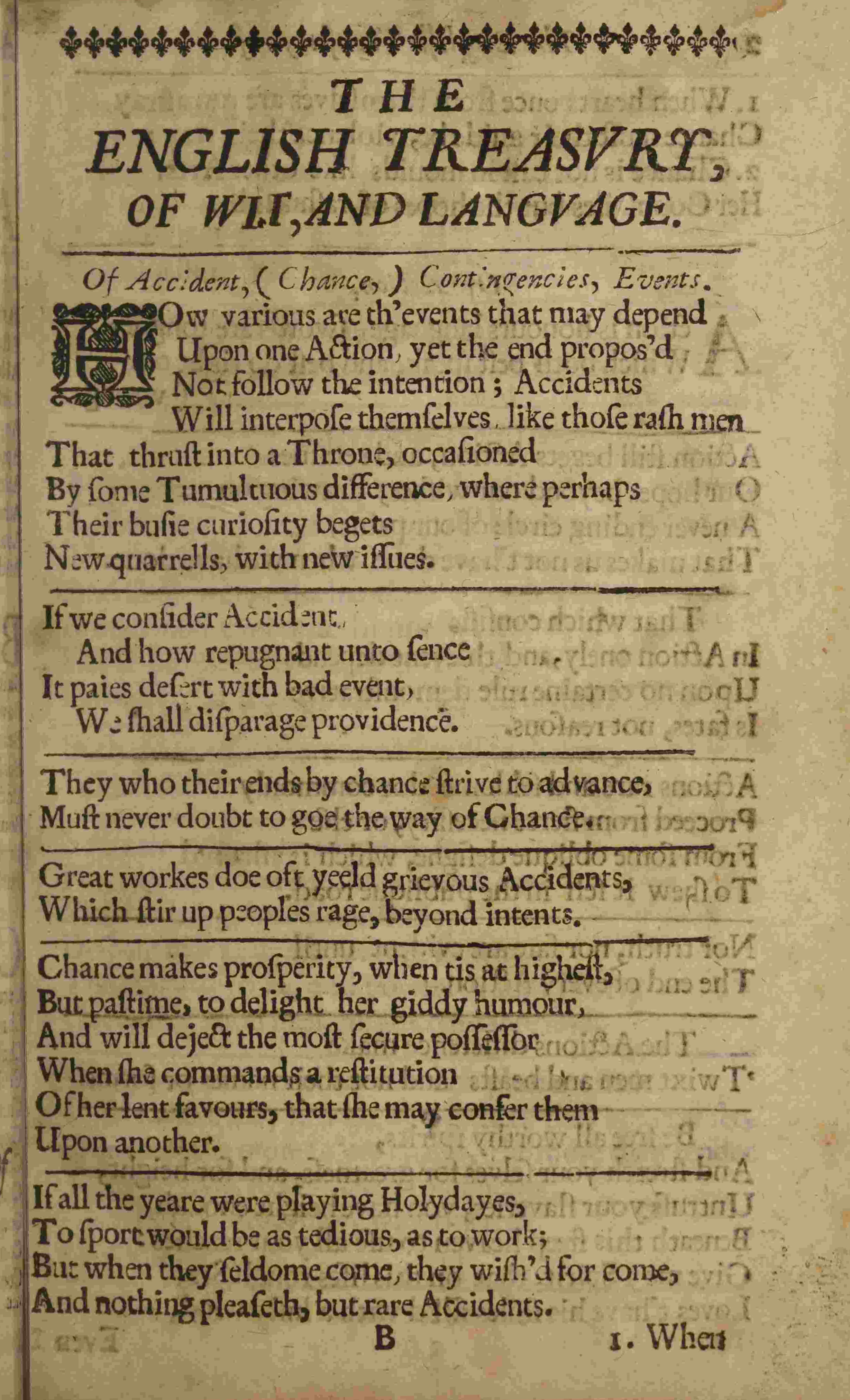

One of the most significant innovations of this project is the implementation of a three-part identification system to describe each extract from Cotgrave’s English Treasury of Wit and Language. Despite some misnumbering errors found in various copies, the majority of English Treasury copies maintain relatively consistent pagination and signing. Arthur E. Case, in A Bibliography of English Poetical Miscellanies 1521–1750 (1935), points out these errors: “Pp. 26 and 292 are misnumbered 12 and 892; in some copies p. 6 is unnumbered, and p. 169 is misnumbered 199” (p. 68). His bibliographical description draws from in-person examination of three copies held at the British Museum (now the British Library), two copies at Oxford University’s Bodleian Library, and a single copy at Harvard University’s Houghton Library. (At least 38 copies of the book are known to have survived and have been consulted for the present study, described in the Copies section ; cf. Estill, “Urge to Organize,” pp. 71–73).

Given the book’s consistent pagination, it becomes practical to describe the page location of each extract without the need for complex signature notation, which is often employed in the description of early English printed books.

Division

Another point of relative consistency lies in the printers’ use of typographic “rules” (ornaments) to divide extracts by page layout and Cotgrave’s general adherence to his printed sources, displaying a reasonable fidelity by avoiding the fusion of separate speeches within a single box. G. E. Bentley, in attempting to determine the true number of extracts in English Treasury, mistakenly guessed the count partly due to the poor quality of a microfilm reproduction. He notes that it is “sometimes impossible to tell whether the passage at the top of a page is a continuation of the last passage on the proceeding page or a new passage,” leading to inadvertent errors such as printing “two distinct passages ... as one, or one passage as two” (p. 194n9). Diligent checking of all passages using digital tools unavailable to Bentley, such as the digital databases of EEBO, ECCO, Literature Online, Google Books, and HathiTrust, has revealed only one instance where a typographic rule was missing. To differentiate these undivided passages, extracts 47.5 and 47.6 are assigned unique identifiers ().

The Formula

Considering these factors, it becomes reasonable to describe each extract using a composite decimal figure, combining its page number (A) with its location on any given page (B) using the formula A.B. To ensure clarity, it is equally important to account for continuations relative to nearby passages, especially when grammar and punctuation leave doubt. In such instances, an en-dash serves as a signal of a partial page range. For example, the case number 190.3– describes a passage from Merchant of Venice that continues from the foot of page 190 to the head of page 191.

Subject Headings

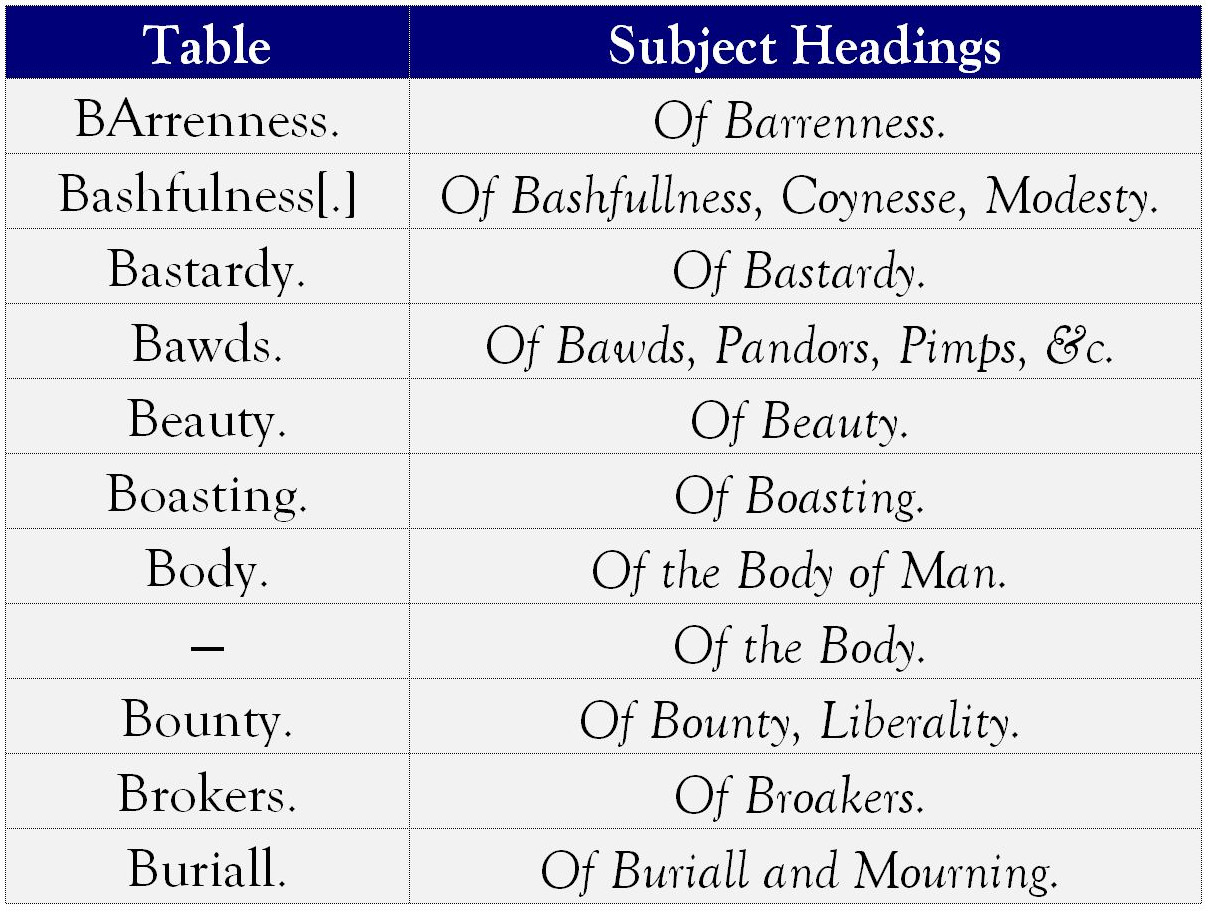

Cotgrave’s English Treasury has 202 different subject headings throughout the book. The “Alphabeticall Table of all the Common Places contained in this Book” lists 200 subject headings (sigs. A4r–v). The main differences between the section headings and the “Alphabeticall Table” occur in “Body,” which stands in for “Of the Body of Man” (pp. 30–31) and “Of the Body” (pp. 31–32), as well as “Love,” which combines “Of Love” (pp. 174–81) and “Of Love and Lovers” (pp. 177–81). These differences add two more subject headings that elaborate on specific aspects of particular themes. The section headings also cover about 87 ‘multifaceted’ subjects. For example, while the table of contents lists “Accident,” the section for this topic in the book elaborates it as “Of Accident, (Chance,) Contingencies, Events” (pp. 1–2). Some table headings use different main terms from those in the section headings. For instance, “Indeavour” corresponds to the section “Of Industry, Indeavour.”

In Cotgrave Online, comprehensive section headings are consistently used. When displayed in alphabetical order, the search algorithm arranges them without including the words “Of” or “the” that precede topic words in certain headings. This feature is exemplified in headings like “Of Action” (pp. 2–9) and “Of the Church and Church-men” (pp. 44–46). While Cotgrave originally employed italic letters in some of these headings, the project presents them in a standard typeface for the sake of simplicity.

For scholars wanting to compare the one-word headings in the “Alphabeticall Table” to the detailed section headings in the book, a CSV file is available ().

The Facet Search and Edition Search offer two searchable author options: “Modern Attribution” (the default setting) and “Original Attribution,” which can be accessed through links next to the ‘reset’ button. The “modern attribution” function derives attributions from Martin Wiggins’s British Drama: A Catalogue, 9 vols (2012–), while the “original attribution” presents information sourced from the playbooks within Cotgrave’s hypothetical library (i.e., title-page statements and signed epistles). Both systems possess certain features that warrant consideration.

- The “original attribution” feature does not expand initials found on a playbook’s title-page, even if the author’s identity is evident. For example, the initials “T.M.” on the title-page of Antigone remain unchanged, even though they clearly signify “Thomas May.” Similarly, the initials “P.M.” and “N.F.” on the title-page of The Fatal Dowry, referring to “Philip Massinger” and “Nathan Field,” remain unexpanded. However, the “original attribution” function identifies “Lewis Sharpe” as the author of The Noble Stranger, despite only his initials appearing on its title-page, because he signed the dedication with his full name.

- Some plays lacking a title-page declaration of authorship are attributed to an author within the “original attribution” feature based on their inclusion in a play collection. For instance, the “tragic” version of Bussy D’Ambois was published without Chapman’s name on its title-page. However, it was included with five other plays in a “nonce” collection with a general title-page declaring authorship as “WRITTEN By George Chapman” (1652). This association of Chapman’s name with the play occurs despite its absence of individual attribution.

- The “original attribution” feature of the project gives precedence to authors associated with individual playbooks, disregarding later claims of authorship made in play collections. For instance, the play Monsieur Thomas (1639), initially published under John Fletcher’s name, and Two Noble Kinsmen (1634), originally published as a play by John Fletcher and William Shakespeare, were later printed in Beaumont and Fletcher’s Fifty Copies and Tragedies (1673). In these cases, only the “original attributions” from the quarto playbooks are acknowledged.

- The “original attribution” search option includes attributions that contemporaneous readers, such as Cotgrave, might have identified as incorrect or incomplete. For example, the play The Coronation is attributed to “John Fletcher” based on his name appearing on its title-page. However, James Shirley later refuted this in his play collection Six New Playes(1653), stating that the play was “Falsely ascribed to Jo. Fletcher”. Similarly, the play The Queen of Aragon is categorized among anonymous plays in the “original attribution,” since William Habington is listed as its author in the Stationers’ Register but not within the playbook itself.

- Modern authorship ascriptions from Wiggins’s British Drama are included without the detailed commentary he provides in the “modern attribution” option. This is particularly noticeable in plays published in Beaumont and Fletcher’s folio of 1647, where numerous collaborations between Beaumont and Fletcher are attributed to Fletcher and Massinger. Additionally, plays attributed to Thomas Middleton receive minimal acknowledgment as a contributor in “original attribution” due to many of his works being published anonymously. Users should take this into account when reviewing search results and consult both Wiggins's catalogue and the Oxford Middleton project separately for comprehensive information.

- In cases where a playbook presents multiple issues with varying authorship information, all authors are included in the search results for “original attribution”. For example, the play The Insatiate Countess has several issues featuring John Marston’s name on the title-page (e.g., 315a), while issue 315cII attributes it to “Lewis Machin, and William Barkstead.” Similarly, the play known as The Bloody Brother in the 1639 quarto and Rollo, Duke of Normandy, in the 1640 quarto, presents multiple assigned authors. The first quarto displays the initials “B.J.F.” on its title-page, while the second attributes the play solely to “John Fletcher.” All these authors are accounted for in the search results under “original attribution,” with the former listed under “B” instead of “F,” assuming that the initials refer to different authors rather than a compound name.

- To ensure complete transparency, the following table details instances where the “modern attribution” and “original attribution” yield different search results.

Authors:

XLSX

Titles

- In the Facet Search and Source Index, only primary titles of plays are included, based on entries from the revised third edition of Alfred Harbage’s Annals of English Drama (2nd ed. 1964; rev. 1989).

- In the Edition Search and Data, secondary titles for plays are included, based on secondary titles provided in Harbage’s Annals of English Drama.

- In the Source Index, additional signifiers are added to help users find the titles of certain plays. For example, to distinguish plays with the same title as another work from Harbage’s Annals, a genre term or the author’s name is sometimes added. For instance, to specify references to Shakespeare’s “Richard II” and “Julius Caesar,” the title entries add Shakespeare’s name alongside the title, such as “Richard II, by William Shakespeare” and “Julius Caesar, by William Shakespeare.” This is necessary because other authors wrote their own plays about these celebrated historical figures.

- In the Facet Search, Edition Search, and Source Index, titles have articles (both indirect and direct) and genre terms removed for most plays. However, a genre term is sometimes added to distinguish plays with similar titles. For example, “Bussy D’Ambois” is identified as “Bussy D’Ambois [Tragedy]” to distinguish it from its sequel, “The Revenge of Bussy D’Ambois,” identified as “Bussy D’Ambois [Revenge].” The same convention is used for the “Conspiracy” and the “Tragedy” of “Charles Duke of Byron.”

- In the Edition Search, the secondary title of a play may occasionally be given with a date of its own. For example, in the entry “Bloody Brother [Rollo, Duke of Normandy, 1640] {1639 or 1640}” the date “1640” within the square brackets refers to the publication of the play in 1640 under the alternative title “Rollo, Duke of Normandy.” Other alternative edition titles include Brennoralt (1646), previously published as “The Discontented Colonel” (1642), and Wonder of Women (1606), reissued in the same year with the alternative title “Sophonisba.”

- The Edition Search and Source Index occasionally append speculative statements about the sources of certain plays. For example, “City Wit; or, Woman Wears the Breeches” includes the critical speculation “{unknown ed, or ms; print 1653}”. This refers to a conclusion drawn in the forthcoming scholarly edition of English Treasury, which suggests that Cotgrave may have used a copy different from the 1653 edition for his quotations of this play. Similarly, there is the entry “Mayor of Quinborough [Hengist, King of Kent, MS] {unknown ed, or ms; print 1661}”. This entry refers to G. E. Bentley’s conjecture that Cotgrave had access to a lost manuscript copy of Middleton’s Mayor of Quinborough.

- In the Editions section of the web project, Cotgrave’s sources are referred to by their original, non-modernized titles.

Dates

- A date without brackets denotes a play published in a single edition before 1655 (e.g., “Family of Love 1608”).

- A date or multiple dates enclosed in curly brackets or braces indicates a play published in multiple editions, where the evidence suggests either a single edition as Cotgrave’s source (e.g., “Coriolanus {1632}”) or the possibility of more than one source edition (e.g., “Henry VIII {1623 or 1632}”).

- Square brackets are used to provide critical commentary, especially related to the text of the play or the editions of the source, as described in Greg’s Bibliography.

- References to “A-text,” “B-text,” or “C-text” pertain to the play’s “text” and are independent of edition information. These letters are based on the sequence of creation determined in Martin Wiggins’s British Drama (2012–).

- When “BEPD” is mentioned, it refers to W. W. Greg’s A Bibliography of the English Printed Drama to the Restoration (1939–1959). It is applied in cases where a playbook lacks a publication date or when more than one edition was published in the same year.

- Date ranges accompanied by “eds” (e.g., “Romeo and Juliet {1599–1637 [6 eds]}”) indicate the possibility of a specific number of editions that could have served as Cotgrave’s source. The number refers to editions published within the specified date range.

HOW TO CITE

Please cite this resource using its URL, including any specific component in brackets or described (e.g., Facet Search, Edition Search, Source Index, Subject List).

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

All content on this subpage of The Shakespeare Authorship Page is protected under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License Agreement. For specific terms of use, which require acknowledgement of authorship and citation of any data extracted from the site for derivative scholarship, please refer to CC BY-NC 4.0 International.